In search of the

mountain giants

“All the progress I’ve witnessed relies on the generosity of our supporters, particularly those in the UK”

Nicola Loweth,

India and China regional officer

In 2015, China announced the results of its fourth national panda survey. It reveals really encouraging news – an increase of 16.8% in wild panda numbers since 2004. WWF’s Nicola Loweth visited some remote mountainous regions of China to find out how our supporters’ generosity has helped to boost the prospects of this iconic species.

Giant pandas are rarely seen in the wild so as I head to south-west China’s Shaanxi and Sichuan provinces, I know my chances of spotting this incredible animal are extremely slim. In 10 days I travel 1,200km, visit seven nature reserves and 10 project sites, meet many amazing and dedicated people, and experience my first earthquake. Read on to find out how close I come to an encounter with those elusive pandas…

Infrared cameras and sustainable tourism

My journey begins in Chengdu, the provincial capital of Sichuan province – a city famous for its tea houses, its spicy, tongue-numbing hotpots, and of course giant pandas!

Having spent my first night in a hotel called Wong Impression, I head to the beautiful Qionglai mountains, to Anzihe Nature Reserve. It’s important because it connects four nature reserves – Wolong, Heishuihe, Fengtongzhai and Labahe. Together these reserves protect 877,980 hectares of panda habitat.

I meet Wang Lei, the head of the reserve, who explains how our support has made a real difference. We first supported Anzihe in 1998, with technical support on forestry monitoring. Since then we’ve helped rebuild the ranger station after it was damaged by the 2008 earthquake and built an eco-friendly education centre which is visited by hundreds of schoolchildren each year.

I also see the mini-hydropower generator which we supported and the new artificial wetland that treats waste water from the patrol stations and the education centre. Practical solutions such as these, which are being constructed in nearby communities as well as nature reserves, help to reduce human impacts on the panda habitats.

With our support, infrared cameras were introduced in the reserve in 2012. Wang Lei explains how the camera traps have been used to monitor wildlife and improve their knowledge of pandas in the reserve. This recent footage of a male panda marking his territory by doing a handstand is a wonderful example.

Tourism is on the increase throughout south-west China – nearly 1,000 visitors came to Anzihe last year. The vast majority are domestic travelers escaping the heat of the cities. But unregulated tourism is threatening panda habitats, so we’re working with the provincial authorities to develop a sustainable tourism industry that protects biodiversity and the environment.

Community protection

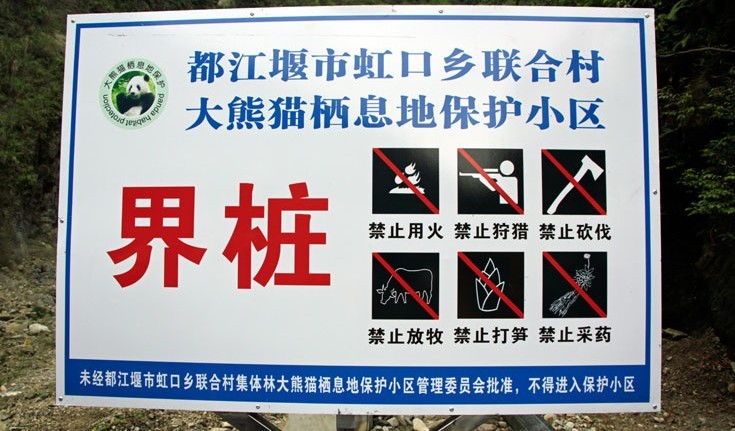

Communities play an important role in managing panda habitats. I visit Lianhe village where, with our support, the community collectively manages 300 hectares of panda habitat that connects two panda nature reserves – Longxi-Honkou and Baishuihe.

Zhou Huagang, the village leader, explains that after the protection zone was founded, local people organised their own community patrolling teams and put signs on the boundary of the community forest to stop illegal logging, poaching and bamboo shoot collection.

Earthquake and forest development

I’m woken by an earthquake measuring 4.8 on Richter scale. It’s a stark reminder of the volatility of the area. On 12 May 2008, a magnitude 8.0 earthquake had a profound effect on local communities, killing over 70,000 people. It also badly affected the natural environment – an estimated 1,220 sq km of forest, grassland and wetlands were destroyed by the earthquake and subsequent landslides.

We’re here to celebrate the official opening of a new wildlife protection division in one of the largest forest development corporations in Sichuan province. It’s the first time a former logging company has established its own protection unit, with responsibility for implementing biodiversity conservation in 700 sq km of panda habitat.

Historically, Pingwu Forestry Development Corporation’s main source of revenue was timber. But when the Chinese government banned logging in panda habitats, in 1998, the corporation had to shift its focus. We’ve been helping the corporation’s staff by sharing our technical expertise on conservation management, corridor restoration and anti-poaching activities.

As we head towards Wanglang Nature Reserve, we pass several dams and hydropower stations. Large areas of panda habitat have been flooded – something that’s further isolating panda populations.

Panda poo

Wanglang is one of China’s oldest panda reserves. Established in 1965, it covers 320 sq km and is home to about 32 pandas, as well as other endangered species such as black bear, red panda, musk deer and golden monkey – and many species of trees, shrubs, grasses, ferns and other plants.

As we climb to 3,000 metres above sea level, in less than an hour we identify more than 10 different species of orchid!

And there’s plenty of bamboo. It’s not the best time of year to look for pandas but I’m still optimistic. Finally, when it’s almost time to head back, our guide spots a panda dropping.

Survey teams rely heavily on panda droppings to count the number of individuals in an area. Chinese researchers have found that pandas have varying average bite sizes. So by measuring the average bite size of the bamboo fragments in droppings, they can determine the minimum number of pandas in a given area.

Panda road safety

My next stop is Guanyinshan Nature Reserve – a former forest farm on the southern slopes of the Qinling mountains. These mountains contain the watershed of China’s two main rivers, the Yangtze and the Yellow. Forests and wetlands here are home to red pandas, Asiatic black bears, yellow-throated martens, takin, blue-eared pheasants and my personal favourite – the golden monkey.

The reserve was intensively logged until 1998. But thanks to WWF, Shaanxi Forestry Department and Guanyinshan Nature Reserve it’s now being restored, and bamboo has been planted. With our support, the nature reserve was recently awarded ‘national nature reserve’ status, which means it’ll be given more resources to support conservation activities.

Near a road that runs through the Qinling mountains, I visit a restoration site that connects one nature reserve to another. Chenghongfei, the vice-director of Guanyinshan Nature Reserve, explains that in 1999, sections of this road were upgraded and a tunnel was built that left 13km of mountain road abandoned. With support from us and more than 40 local people, they’ve started to restore the habitat by planting 1 sq km of arrow bamboo which is the pandas’ main and most nutritious food source.

I’m also shown an ecoduct demonstration site, where 10 passages have been constructed to allow wildlife to cross safely. Camera traps have been set up beside the ecoducts so we can monitor their effectiveness. The team checks the cameras and shows me evidence of takin and leopard cats.

Ironically, we spy panda droppings on the road. A panda has travelled across the road rather than using the new ecoduct. Typical!

Latest national panda survey

My next stop is Laoxiancheng Nature Reserve. Laoxiancheng used to be the county town with a population of over 30,000, but it was abandoned over 100 years ago when bandits rampaged the town and two county governors were killed. Now it’s a village with fewer than 130 people. The only traces of its legendary history are its city wall and beautiful ‘west gate’.

In ancient times the forest around this area was heavily logged, but when the people left, the forests restored themselves. It’s now a haven for wildlife.

As we head deep into the forest I ask Liyuepeng, a ranger at the reserve, about the fourth national panda survey – the first since 2004. The Chinese government announced the results early in 2015, but the field work took place here over two years earlier. Liyuepeng remembers that conducting the survey was difficult because the snow was so deep – but they found panda droppings almost every day, so they were optimistic about the results.

Contemplating conservation challenges

My 10 amazing days here have allowed me to challenge the field team on their strategies, quiz the nature reserve staff about patrolling and monitoring – and sample some pretty strange cuisine. I’ve also made some fabulous new Chinese friends. And of course I’ll treasure my close encounters with offerings left by those elusive giant pandas.

But as I prepare to head back home, I find myself musing on how all the progress I’ve witnessed relies on the generosity of our supporters far from China’s mysterious mountain forests – particularly supporters in the UK. It’s thanks to you that we’re able to support nature reserves, state-owned forest farms and local communities to develop long-term solutions to protect pandas in the wild. Very real threats still remain, but we’ve achieved a lot in our quest to ensure that a global conservation icon is protected for future generations.